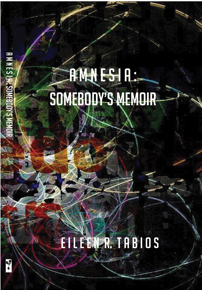

AMNESIA: Somebody’s Memoir

by Eileen R. Tabios

a review by Valerie Morton

Amnesia: Somebody’s Memoir by Eileen R. Tabios (Black Radish Books, 2016) is a very bold poetic achievement by a poet and writer whose work I have come to admire and who constantly surprises with her adventurous experiments with new forms.

Amnesia is a major accomplishment—a single poem of 1,146 lines written in response as the poet read through her many previous works, using a computer program-inspired but actually manually-generated process (which is explained at the back of the book). I first became aware of this process when reading the poet’s previous collection—The Connoisseur of Alleyways (Marsh Hawk Press, 2016). As a British poet schooled in traditional forms I realize how restricting they can be unless you are prepared to experiment in the broadest possible sense without losing the imagery and musicality that for me is “poetry.”

In this extraordinary work Eileen Tabios has brilliantly achieved such a result so that whichever way I read and in whichever order, I end up with the same emotional response.

One of the first things I noticed on opening the book was the “unorder” of the chapter headings but this quickly left my mind as I began to find myself instinctively translating words into other words—like tossing a coin—beginning with “amnesia” itself (forgot/remembered). Whichever way the words and phrases are turned or repeated their intention is clear—the universality of memory. It is all here—life/death . . . hope/despair . . . war/peace . . . love/hate and so much more.

Each chapter is a poem in itself, and yet each line could be interchangeable with others from any part of the book, and still provide meaning, and it soon becomes apparent that the order is irrelevant. Becoming immersed in this book transported me into a theatre—a theatre where the stage is the world—enormous and filled with over 200,000 years of human existence, interconnected by common experiences. From my seat in that audience I was able to watch the spotlight light fall on a different persons as I read each line—I forgot “the grandmother who was too old to run” . . . “water becoming like love: miserable and lovely” . . . “a smiling stranger across the street . . . the angel with rust in his voice” . . . “the killer nicknamed ‘Bullet’ for his bald head and thick neck” until it all gelled into one—one world, one common denominator (being human).

So often we forget that we all come from the same place, are gifted with the capacity to create a bond or to divide. We do have choice—we CAN always remember if we want to—memories diminish only if we let them.

In such a collection, so rich in its breadth and diversity, it has been difficult to choose a cross-section of examples. It is not always comfortable reading, but that is its strength—we could all “be” anybody and recognizing this is at the heart of its conceit:

Chapter 25: I Forgot the Binary of Refugees Vs. Art

I forgot men holding babies upside down by their legs

to smash them across the same trees that received

their piss.

I forgot the collapse of New York City Towers—I forgot

inhaling their spines to become mine in the aftermath.

I forgot the map crafted from skulls.

I forgot the anguish of knowledge.

Chapter 20: I forgot Quaffing Sweet Jerez, and

Wings Flared As If Posing for Rembrandt (aka I

Remember You, Philip Lamantia)

I forgot Heaven could be . . . a breath away.

I forgot I ignored Paris waiting on the other side of

a shuttered window.

I forgot a sarong fell and a river blushed.

I forgot whispering to the daughter borne from rape

“Regret is not your legacy.”

I forgot the votive candle flickering within my navel.

I forgot the inevitability of ashes.

Chapter 17: I Forgot the Logic of Amnesia—illustrating

how the mind can work its way round—“I know who my

father isn’t, so I must know who he is.”

I forgot my father is not and never has been the president

of the United States

is not Joseph Stalin

is not Pol Pot

is not Benito Mussolini

is not Saddam Hussein

is not Idi Amin

is not Joseph Goebbels

is not Adolf Hitler

There is no real logic in who and when and where we are born.

Chapter 13: I Forgot the Spiral That is Memory’s

Perspective

I forgot the awkward blanket of trust.

I forgot ivory.

I forgot the deception of diamonds.

I forgot the joker card.

There were occasions when I found the constant repetition of “I forgot” a distraction from some of the beautiful and stunning poetic imagery such as:

I forgot a flock of starlings shattering the sky’s clean

plate like grains of black.

I forgot the summer-dusted landscape of Gambia.

I forgot we agreed to live in Technicolor.

l forgot love stutters over a lifetime.

I forgot you were the altar that made me stay.

I forgot the room intimate with piano lessons.

I forgot the unknown source of a lover’s pause.

At the back of this book is an interesting explanation of what Eileen Tabios calls “Babaylan Poetics” (the Babaylan was a pre-colonial Filipino community leader ‘endowed with gifts of healing, foretelling and insight’) and how her “poetry generator” reflects the re-creation of language as a means of identification. This has long been a subject which has interested me in the sense that one of the first needs of any “diaspora” seems to be the creation of an identifying language—a variation in pronunciation or syntax. Here in Amnesia Eileen Tabios takes this further—an “unpicking” of language in order to lose the “borrowed tongue” of colonialism, a tool for transforming language back to its own. A “re-creation” of identity.

The importance of the reader in Babaylan poetics is recognised through the interesting “response” section at the end of the book where six poets were asked to respond to Chapter 6: I Forgot the Plasticity of Recognition—six totally different responses, from different perspectives, four substituting “I remember” for “I forgot” and it is particularly interesting to note how the remember/forgot melt into one in interpretation, however random they may appear on the page. The poet-respondents are John Bloomberg-Rissman, Sheila E. Murphy, lars palm, Marthe Reed, Leny M. Strobel and Anne Gorrick.

Here is a book that challenges our perceptions of “memory” in that what we think are our own memories are also “universal” memories, belonging to collective humanity and if we can “remember” then maybe we can move on to communion rather than division. It offers a way out of prejudice, fear, rejection—handing us a basic, most simple key, to recognition of each of us as one, not as other. The world is becoming a smaller place as we discover more about the Universe—we are a mere dot on the larger canvas and if we want to survive we must unite. We need to widen our interpretation of “belonging.”

In the words of this exciting poet, from Chapter 24: I Forgot the Shadow of Gray

But I will never forget we walk on the same planet

and breathe from the same atmosphere. I will never

forget the same sun shines on us both. I created my

own legacy. No one is a stranger to me.

It is a privilege to have reviewed this work which has left me with much food for thought and changed my own perception of the world. It is much more than a poetry collection—it is a clear invitation to re-join the human race and view it as our own rather than belonging to someone else. A highly recommended read—not to be missed.

Valerie Morton is a British poet whose work has appeared in various magazines and anthologies in the UK and USA and has won or been placed in a number of competitions. She has two collections published by Indigo Dreams Publishing: Mango Tree (2013) and Handprints (2015). She has taught Creative Writing at a mental health charity and during 2016 been Poet in Residence at the Clinton Baker Pinetum in Hertfordshire. A member of Ver Poets she contributed to their Healing Poetry event in October 2016.