Poems

Nina Kossman

First, you sell your time.

(This is called “earning a living.”)

Then you sell your ideas.

(This is called “being famous.”)

Then you sell your house.

(This is called “moving up.”)

Then you sell your wife of twenty five years.

(This is called “a midlife crisis.”)

Then you sell your old books.

(This is called “becoming a real Buddhist.”)

Then you sell your old friends.

(This is not called anything special.)

Then you sell your old clothes.

(This is called “crossing the threshold” or simply “poverty.”)

Then you sell your conscience.

(“But, ma’am, we don’t use this word here . . .”)

MY OLD BELIEFS

When I was five, I believed in Communism.

When I was eleven, I believed in Zionism.

When I was nineteen, I believed a man.

When I was twenty-three, I believed in death.

When I was thirty, I believed in myself.

When I was thirty-nine, I believed in time.

Disillusioned with all of them,

I believe in something else now,

I won’t tell you what.

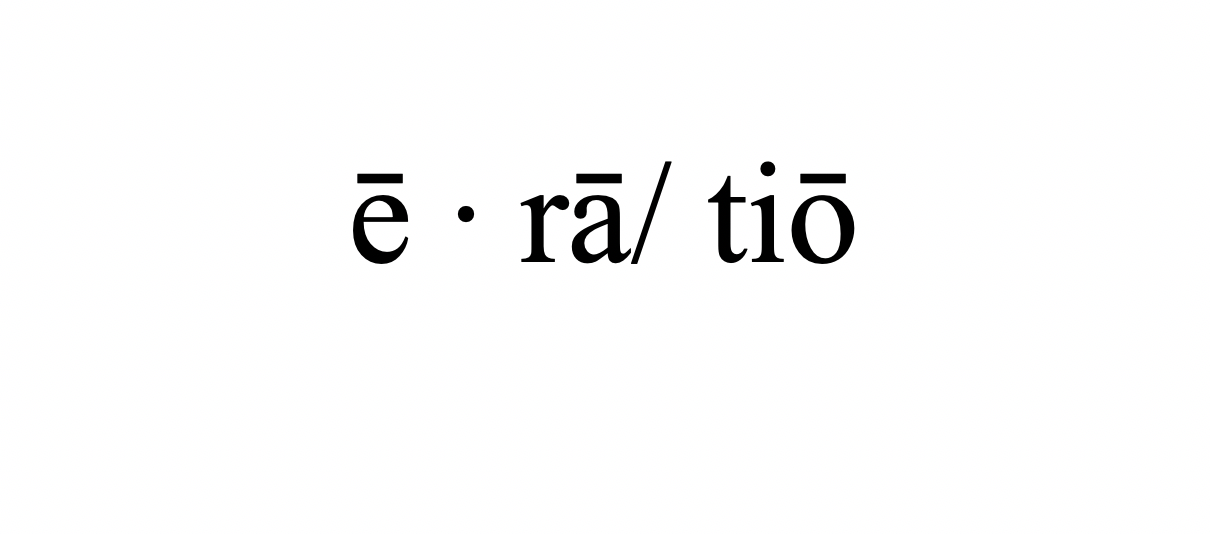

WOE FROM WIT *

“Woe from Wit” is a famous Russian myth.

Woe from thinking too much.

Woe from feeling too deeply.

Woe from not feeling deeply enough.

Woe from saying too much.

Woe from not saying enough.

Woe from not saying anything.

Woe from writing your thoughts.

Woe from writing down others’ thoughts.

Woe from not writing anything.

Woe from being different.

Woe from being the same.

Woe from praying to a wrong god.

Woe from praying to the right god.

Woe from not praying at all.

Woe from God.

Woe from man.

Woe from woman.

Woe from a tyrant.

Woe from a crowd that obeys a tyrant.

Woe from a crowd that disobeys a tyrant.

Woe from a pin on your school uniform with the little Ulianov boy.

Woe from not wearing a pin on your uniform with the little Ulianov boy.

Woe from thinking too subtly.

Woe from thinking too plainly.

Woe from not thinking at all.

Woe from knowing that the author of “Woe from Wit” was torn apart by a madding crowd in Tehran.

Woe from it all.

* “Woe from Wit” is a famous play by Griboedov (1795, Moscow, Russia – 1829, Tehran, Iran).

A LIST OF MY FAILURES

When I was four, I failed at eating a zapekanka*.

When I was five, I failed at waking up Lenin.

When I was eight, I failed at being an Oktyabryonok*.

When I was ten, I failed at being totally Russian.

When I was eleven, I failed my motherland.

When I was twelve, I failed at speaking Hebrew like my classmates.

When I was thirteen, I failed my second motherland.

When I was fourteen, I failed at losing my soul.

When I was fifteen, I failed at substituting my soul with empty words.

When I was sixteen, I failed at remembering.

When I was seventeen, I failed at forgetting.

When I was nineteen, I failed at becoming myself.

When I was twenty-one, I failed at losing myself.

When I was twenty-three, I failed at nothing. (Just kidding!)

When I was thirty, I failed at refusing to work.

When I was thirty-nine, I failed at all those things

I didn’t manage to fail at earlier. When I was forty . . .

The list of my failures is long, but life is not over yet,

There’s plenty of time to fail at everything yet again.

* “zapekanka” — a classic Russian breakfast dish. It was often served cold in Soviet kindergartens.

* “Oktyabryonok” — a child Communist in the Soviet Union. Being an “okyabryonok” was mandadory.

There are writers who are so afraid their readers might steal their ideas, that they end up not writing anything at all.

There are publishers who are so afraid that someone might steal their books, that they don’t place their books in bookstores.

There are women who are so afraid that men will steal their virginity, that they don’t have any relationships with men at all.

There are women and men who are so afraid their children will be unhappy, that they decide not to have any children.

There are individuals who could pull their country out of a quagmire, but they are so afraid to be blamed for their country’s impending doom, that they don’t take any steps towards becoming its leaders.

Fear is a potent power, no less than its opposite, brainless courage, and because of it many things that could help us are never born.

Too ripe, this pear,

too brown and sweet,

and these grapes are almost raisins.

When a brown pear falls,

no one pities it:

so many pear trees in the orchard.

An old woman stumbles,

falls and then dies;

if no one cries for her,

the world ends.

When he bade farewell to his life,

he said: do not ask for condolence

from men of perpetual surface —

words of depth cannot issue

from mouths so accustomed to verbiage,

nothing comes from them when confronted with loss,

nothing but ribald jokes or nonsense language.

The flippancy of the mind is endless, he said.

Damned if you do and damned if you don’t;

damned if you are silent and damned if you speak;

damned if you are alive and damned if you are not —

this is the premise on which all things are based,

things that are upright and things that fall,

things that bow in the wind and things that are free

of the intolerance of the perfect and the wrath of the meek,

the tediousness of love and the intensity of loss . . .

At this point he stopped breathing and was done with life.

Moscow born, Nina Kossman is a bilingual writer, poet, translator of Russian poetry, painter, and playwright. Among her published works are two books of poems in Russian and in English, two volumes of translations of Marina Tsvetaeva’s poems, two books of short stories, an anthology published by Oxford University Press, several plays, a book of poems in English, and a novel. Her work has been translated into Greek, Japanese, Russian, and Spanish. She received a UNESCO/PEN Short Story Award, an NEA fellowship, and grants from Foundation for Hellenic Culture, the Onassis Public Benefit Foundation, and Fundación Valparaíso. She lives in New York.